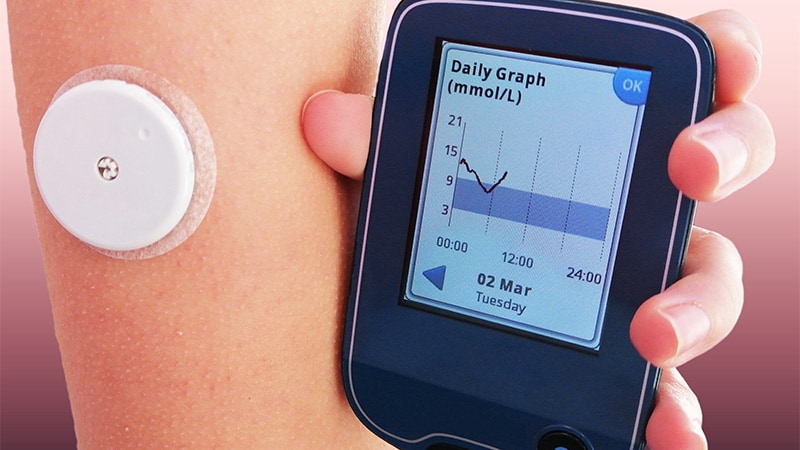

Is Continuous Glucose Monitoring for Everyone With Diabetes?

STOCKHOLM, Sweden — Whether continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) is for “all” — and if not, for whom — was the topic of a lively debate at the recent European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) 2022 Annual Meeting.

In the debate, the two participants generally agreed that CGM is appropriate for all people with type 1 diabetes and those with type 2 diabetes on intensive insulin regimens.

Most of the discussion centered on people with type 2 diabetes on less intensive treatments and other subgroups.

Use of CGM Is Growing

Maciej T. Malecki, MD, PhD, of the department of metabolic diseases, Jagiellonian University Medical College, Krakow, Poland, argued the “yes” side. He observed: “CGM is not a tool for every patient with diabetes. However, large groups of patients with diabetes benefit from its use. The use of CGM will be growing rapidly as new technologies develop and prices go down.”

He began by listing the advantages of CGM, including improved glycemic control, safety in the form of alarms for low glucose levels, avoidance of the inconvenience of fingerstick glucose monitoring, and the capacity of CGM to enable closed-loop insulin delivery, also known as artificial pancreas systems.

There’s plenty of literature at this point on the advantages of CGM in type 1 diabetes. Just today, a new study has been published in the New England Journal of Medicine detailing results of the FLASH UK study. In the trial, among 156 participants with type 1 diabetes and mean baseline A1c around 8.6%, those randomized to the intermittently scanned FreeStyle Libre 2 (Abbott Diabetes Care) experienced a 0.5 percentage point greater drop in A1c at 24 weeks compared with usual fingerstick blood glucose testing (P < .001), and they spent 43 minutes less time in hypoglycemia per day.

In Stockholm, Malecki described a 7-year follow-up study published in January showing that CGM initiation within 1 year of type 1 diabetes diagnosis results in improved long-term A1c compared with starting later or not at all. And another trial reported in 2019 found that it is real-time (ie, not intermittently scanned) CGM, regardless of the method of insulin delivery (pumps or injections), that makes a therapeutic difference in people with type 1 diabetes.

And earlier this year, a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials confirmed the superiority of CGM to fingerstick monitoring in people with type 1 diabetes, especially for those with baseline A1c levels above 8% (64 mmol/mol).

In pregnant women with type 1 diabetes, the randomized controlled CONCEPTT trial showed improved outcomes in terms of neonatal birthweight and infants’ hospital length of stay with CGM use compared to fingerstick monitoring.

As for people with type 2 diabetes, in the DIAMOND trial, adults aged 60 years and older with type 1 (n = 34) or type 2 diabetes (n = 82) on multiple daily injections both saw A1c reductions with CGM.

Meanwhile, in a single-arm study of adults with type 2 diabetes treated with just basal insulin or non-insulin therapy, use of CGM for 6 months significantly improved time-in-range and A1c, regardless of the number of medications patients were taking. The authors of that study write that their and other data suggest “insurance eligibility criteria should be modified to expand real-time CGM use by type 2 diabetes patients treated with less intensive therapies.”

And in real-world German registry data, which included 1440 adults with type 2 diabetes, in patients not on intensive insulin therapy (78%), initiation of CGM led to significant reductions in A1c, body mass index, and severe hypoglycemia. Those authors concluded that use of CGM “may be associated with improvement in treatment adherence, changes in diet, and increased physical activity through CGM readings.”

Evidence also supports use of CGM in hospitals, including a recent randomized trial of general medical and surgical inpatients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes on insulin, which showed significant reductions in hypoglycemia using CGM to guide insulin adjustments compared with those on point-of-care resulting in significantly fewer hypoglycemia events.

Malecki also reviewed data showing the benefits of CGM on maternal and neonatal outcomes in gestational diabetes, older people with memory problems, transient neonatal diabetes, and diabetes secondary to total pancreatectomy.

He concluded: “There is a growing body of evidence that CGM also improves glycemic control in type 2 diabetes on less intensive hypoglycemic therapy. Further data, including cost-effectiveness and quality of life, are needed. However, one may expect that the use of CGM in this patient group will be growing.”

How Convincing Are the Data for Those Not on Insulin?

Taking the opposite stance, J. Hans DeVries, MD, PhD, professor of diabetes medicine, University of Stockholm, Sweden, began by citing a real-world retrospective, data analysis, for which Malecki was the lead author, that found patients in Poland typically scan intermittently-scanned CGMs more often and achieve lower A1c levels and higher time-in-range than people with diabetes in other parts of the world.

“It is the Polish physicians. They are just better than we are,” he quipped.

He agreed with Malecki that all patients with type 1 diabetes should be offered CGM, citing the American Diabetes Association/EASD consensus report on the management of type 1 diabetes in adults, which states that it’s the standard of care.

However, he pointed out that while most patients with type 1 diabetes can benefit from CGM, some will choose not to use it. “It’s not suitable for all. Some might not find it valuable. They might find it stressful because they dislike being attached to a device or constantly being reminded of their diabetes or feeling exhausted by alarms.”

He also agreed that CGM is “a closed case” for people with type 2 diabetes who are on basal-bolus insulin therapy, noting that these individuals “aren’t fundamentally different from type 1 patients, so it makes sense that for these patients CGM is very helpful.”

But for those with type 2 diabetes who are only on basal insulin, DeVries said the data are less convincing. For example, in a randomized trial of 175 such patients, there was a significant 0.4 percentage point difference in achieved A1c between those randomized to CGM versus fingerstick glucose monitoring. However, in the supplement, the 24-hour data showed no difference in fasting glucose levels or total daily insulin dose, suggesting “these patients did not use more insulin thanks to the CGM…it is a behavioral intervention.”

And now, DeVries pointed out, a study in which the new once-weekly injectable type 2 diabetes agent tirzepatide was added to insulin glargine in patients with type 2 diabetes suggests an alternative to CGM, as this regimen produced a larger drop in A1c (–1.47 vs –0.4 percentage points) along with significant weight loss (–10.5 kg vs no change) and no alarms. “This is not a difficult choice,” he commented.

Regarding people with type 2 diabetes not on insulin, DeVries pointed to a study from Japan that showed a significant A1c drop in those using flash glucose monitoring compared with fingerstick monitoring. However, one third of those who were assessed for eligibility declined to participate, and of the remaining 100 patients that were randomized, the between-group difference in A1c was just 0.29 percentage points.

“We have to ask, how meaningful is that difference? I don’t think the data are very convincing for patients not on insulin. And that is, of course, the largest group,” he noted.

As for people without diabetes or with prediabetes, he pointed out that the market is potentially huge, as long as the device is non-invasive.

Smartwatches are being developed for all kinds of medical assessments, including heart rate, blood pressure, temperature, sleep patterns, gait, and mobility, in addition to glucose and insulin resistance. About 50 million Americans currently use a smartwatch, he noted.

For people without diabetes, use of CGM can reveal how food affects their blood glucose, which might translate to earlier detection of diabetes or prediabetes and perhaps healthier behavior. And in fact, DeVries said that some key opinion leaders in the field are arguing that every healthy person should occasionally use CGM. “There is of course one huge problem. It is that we have no data on this whatsoever.”

Malecki has reported receiving honoraria for services as a consultant or lecturer from Abbott, Ascentia, Dexcom, and Medtronic. His institution is supported by an unrestricted grant from Medtronic. DeVries had no relevant financial relationships to disclose as of September 2021, as he is seconded for 4 days per week to the European Medicines Agency. None of the statements he made reflect the agency’s point of view in any way whatsoever. In the past, he has had disclosures with Abbott, Afon Technology, Dexcom, Lilly, Medtronic, and Metronom Health.

Miriam E. Tucker is a freelance journalist based in the Washington, DC, area. She is a regular contributor to Medscape, with other work appearing in The Washington Post, NPR’s Shots blog, and Diabetes Forecast magazine. She is on Twitter: @MiriamETucker.

For more diabetes and endocrinology news, follow us on Twitter and Facebook.

Source: Read Full Article