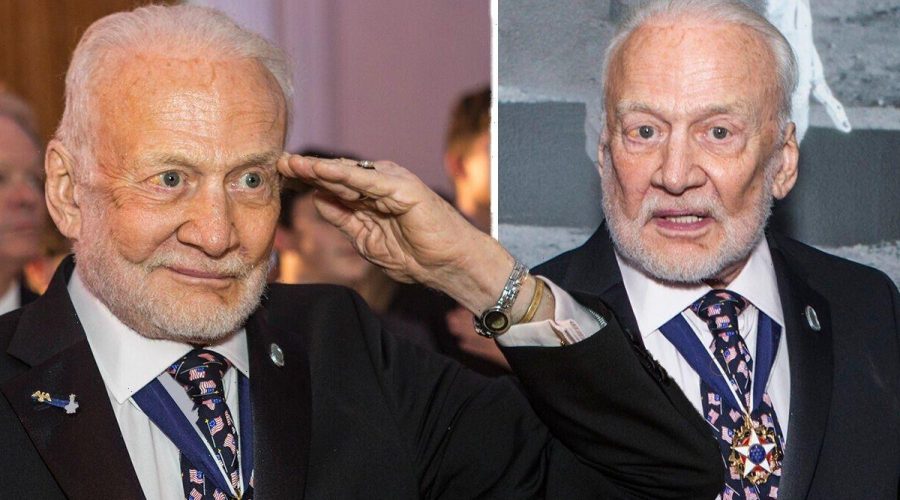

Buzz Aldrin health: ‘Recovery was not easy’ Astronaut, 92, on his past health challenges

Buzz Aldrin discusses impact of cameras during Moon landing

We use your sign-up to provide content in ways you’ve consented to and to improve our understanding of you. This may include adverts from us and 3rd parties based on our understanding. You can unsubscribe at any time. More info

As the Lunar Module Eagle pilot boarded the 1969 Apollo 11 mission to the moon, Aldrin and his commander, the late Neil Armstrong, were the first two people to land on the moon. It instantaneously landed Aldrin in the history books, and became one of the most significant moments in human history. Celebrating 53 years this year since the remarkable achievement, Aldrin’s jacket selling at auction, fetching $2.77m (£2.3m) makes it even more poignant. Yet along with his status as a national treasure, Aldrin’s problems began soon after he landed back on earth. This included alcoholism, depression and two divorces.

Having been continually asked throughout the years if he was bothered about being the “second” not first man to step foot on the moon, Aldrin carries with him a sense of frustration.

During one interview back in 2009 he called the label “degrading” before going on to explain just how bad things got for him in the early 70s when he returned from the lunar mission.

Having rejoined the US Air Force as a commander of a test pilot school, he quit the armed services at the age of 42. From here he started to heavily drink alcohol, had an affair and suffered from depression.

Eventually, after another short marriage following the breakdown of his first, the star found himself selling Cadillacs in Beverly Hills, dependent on drink.

DON’T MISS: Micky Dolenz health: ‘I’d have taken better care of myself’ Star on his health woes age 77

Speaking about this difficult time in his life and why he felt it happened, Aldrin shared: “I inherited tendencies in different directions [depression and an addictive personality] and those directions, if you feed them with a life of perfection and discipline and then remove that all of a sudden, it’s probably going to go back to some of the more deep-seated concerns about self-worth and achievement.

“You did that as part of a team; what are you doing now? You get a job as a car salesman and you’re a horrible car salesman. What does that do to a person’s ego.

“I wanted to resume my duties, but there were no duties to resume.

“There was no goal, no sense of calling, no project worth pouring myself into.

“I don’t think the Air Force knew what to do with someone who went to the

moon. I was an outsider.

“I was the egghead from academia who got in because the rules had changed. While I looked for validation from my fellow contemporaries, I instead found jealousy and envy. I did not find team spirit. This led to dissatisfaction, an unease.

“What I felt was depression. But there was another trait that had been hidden. Everyone was drinking, and I was too. This led to periods of self-evaluation and concern. ‘What am I doing?’ ‘What is my role in life now?’ I realised that I was experiencing a melancholy of things done. I really had no future plans after returning from the moon. So I had to reexamine my life.”

Suffering from both alcoholism and depression, even to this day Aldrin looks back and credits the time when he asked for help as one of his “greatest challenges”.

He added: “I had a genetic tendency toward alcoholism. [Both of his parents suffered from the disease.] That eventually reached its peak in 1976 and 1977. Recovery was not easy.

“But it has also been one of the most satisfying because it has given me a sense of comfort and ease with where I am now.”

As Aldrin briefly mentioned, alcoholism seems to run in some families. There is a growing body of scientific evidence that alcoholism has a genetic component. In fact, according to the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, children of alcoholics are four times more likely than other children to become alcoholics

However, other factors such as environmental, can play a significant role in some individuals developing into alcoholism. Back in 1990, Blum et al. proposed an association between the A1 allele of the DRD2 gene and alcoholism. The DRD2 gene was the first candidate gene that showed promise of an association with alcoholism.

Subsequent genetic studies have attempted to pinpoint the exact genes associated with alcoholism, but none have produced conclusive results. A number of genes have been identified that play a factor in the risky behaviours associated with alcohol abuse or dependence.

Yet what has been agreed by researchers is the connection between alcoholism and depression. Often, people with depression who drink alcohol will find they start to feel better within the first few weeks of stopping drinking. This is because alcohol affects the chemistry of the brain, increasing the risk of depression. Hangovers can also create a cycle of waking up feeling ill, anxious, jittery and guilty.

Depression can cause both physical and psychological symptoms – and they are different for everyone. Signs to look out for include:

- Continuous low mood or sadness

- Feeling hopeless and helpless

- Having no motivation or interest in things

- Thoughts about harming themselves.

- Changes in appetite or weight

- Lack of energy

- Low sex drive

- Disturbed sleep.

Individuals who are suffering from depression, alcoholism or both can improve both their mental health and physical health by cutting out alcohol entirely. The Royal College of Psychiatrists recommend that for people who need help with both their drinking and depression, it’s usually best to tackle the alcohol first and then deal with the depression afterwards, if it hasn’t lifted after a few weeks.

For confidential help and support call Drinkline on 0300 123 1110 (available weekdays from 9am–8pm and 11am–4pm at the weekend).

Source: Read Full Article