Regenerating the cells that keep the heart beating

Specialized cells that conduct electricity to keep the heart beating have a previously unrecognized ability to regenerate in the days after birth, a new study in mice by UT Southwestern researchers suggests. The finding, published online in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, could eventually lead to treatments for heart rhythm disorders that avoid the need for invasive pacemakers or drugs by instead encouraging the heart to heal itself.

“Patients with arrhythmias don’t have a lot of great options,” said study leader Nikhil V. Munshi, M.D., Ph.D., a cardiologist and Associate Professor of Internal Medicine, Molecular Biology, and in the Eugene McDermott Center for Human Growth and Development. “Our findings suggest that someday we may be able to elicit regeneration from the heart itself to treat these conditions.”

Dr. Munshi studies the cardiac conduction system, an interconnected system of specialized heart muscle cells that generate electrical impulses and transmit these impulses to make the heart beat. Although studies have shown that nonconducting heart muscle cells have some regenerative capacity for a limited time after birth—with many discoveries in this field led by UTSW scientists—conducting cells called nodal cells were largely thought to lose this ability during the fetal period.

Previous research had suggested that neonatal nodal cells lose stem cell-like qualities before birth, giving them negligible regenerative properties. However, Dr. Munshi explained, their regenerative abilities had never been directly tested because there was no way to eliminate only nodal cells in animal models to spur regeneration.

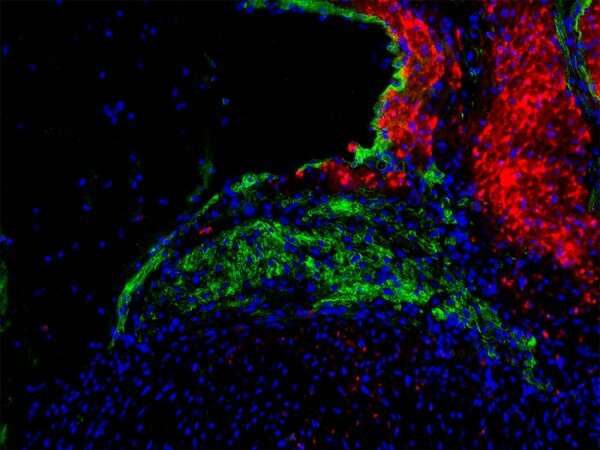

To solve this problem, Dr. Munshi and his colleagues used genetic engineering to develop mice whose atrioventricular (AV) node cells, located near the intersection of the heart’s four chambers, died when they were fed the breast cancer drug tamoxifen. In adult mice of this strain that were given tamoxifen, tissue samples and electrocardiograms revealed progressive heart damage stemming from the death of AV node cells in the following weeks and months. However, when neonatal mice were dosed, heart function appeared to be completely normal in one-third of the animals about a month later.

Taking a closer look, the researchers performed electrocardiograms on newborn mouse models of AV node failure every couple of days after tamoxifen treatment. These tests revealed an initial injury to the heart that gradually healed itself in many of the animals. Although tissue examination showed that this healing didn’t result in a completely normal heart in adulthood, it was sufficient for the mice to have regular heart rhythms.

Intriguingly, further investigation showed that nonmuscle heart cells were the predominant cell type that proliferated after the nodal cells died. These cells appeared to modulate production of proteins that help heart cells make electrical connections.

Why these proteins increased and why only about one-third of the animals showed regeneration remain unclear, Dr. Munshi said. He and his colleagues plan to continue studying the molecular mechanisms behind this phenomenon to gain more knowledge that could eventually lead to a drug that can stimulate the regeneration pathway on demand to regrow damaged nodes in arrhythmia patients.

Source: Read Full Article