Plant-based diet associated with health benefits in heart patients

A high-quality diet that minimizes red meat and processed foods is linked with lower risks of heart attack and stroke in patients with cardiovascular disease, according to a study published today in the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology.

“One of the most common questions physicians receive from patients with cardiovascular disease is what should I eat to improve my health,” said study author Professor Sonia Anand of McMaster University and the Population Health Research Institute, Hamilton, Canada.

“This study in more than 27,000 patients with cardiovascular disease indicates that a high-quality diet emphasizing whole foods and minimizing packaged and processed foods reduces the likelihood of having a heart attack or stroke.”

The study focused on patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) and peripheral artery disease (PAD), who are both at high risk of heart attack and stroke. CAD refers to a narrowing of the arteries supplying blood to the heart while in PAD, arteries in the legs are clogged. PAD is also the leading cause of lower limb amputation. This was the largest study of diet in patients with PAD.

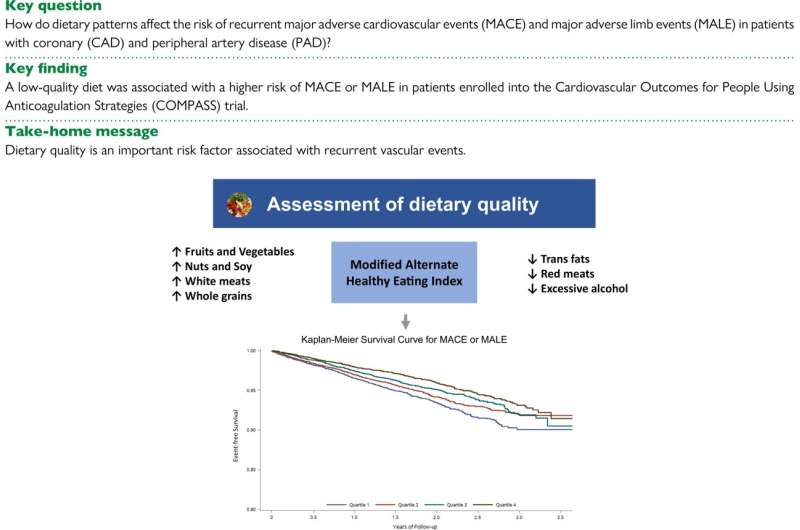

This analysis examined whether diet quality was associated with the incidence of cardiovascular and limb events. Cardiovascular events included cardiovascular death, heart attack and stroke. Limb events included the need for stenting or bypass surgery (to open up a clogged artery in the legs) or amputation.

The study included 26,539 patients with CAD and/or PAD from 33 countries in North America, South America, Eastern and Western Europe, Australia and Asia who were enrolled in the COMPASS trial.2 Of those, 24,119 had CAD and 7,163 had PAD (some patients had both conditions). The average age was 68 years and 78% were men.

Diet was assessed at baseline with a food frequency questionnaire containing all major food groups (dairy, unprocessed and processed red meat, poultry, fish, eggs, whole and refined grains, nuts, fruits, vegetables and soft drinks).

Data from the questionnaire was used to rate diet quality according to the Alternate Healthy Eating Index (0 to 70) and the Mediterranean diet score (0 to 8), which were both modified according to the information available in the questionnaire. Higher scores indicated a better quality diet. The primary composite outcome was cardiovascular and limb events.

During 30 months of follow up, a total of 1,391 events occurred, of which 1,262 were cardiovascular events and 140 were limb events (some patients had both).

The researchers analyzed the association between diet quality and adverse events after adjusting for factors that could influence the relationship including age, sex, country, education level, treatments and medications, body mass index, smoking and other conditions such as diabetes, high blood pressure and heart failure.

Taking the modified Alternate Healthy Eating Index first, the average score was 23. The incidence of recurrent clinical cardiovascular outcomes was highest in patients with a poor diet quality. Each 5-point reduction in the index was associated with a 7% increase in cardiovascular and limb events.

When patients were divided into four groups according to their score, those in the lowest quartile had a 27% increased risk of cardiovascular and limb events compared to patients in the highest quartile. This increased risk was primarily driven by cardiovascular events in those with low diet quality.

Study author Dr. Darryl Wan of McMaster University, Hamilton and the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada said, “Even after adjusting for factors that might affect the association, patients with the worst quality diet had a 27% higher likelihood of vascular complications compared to those with the best quality diet. This excess in risk seems to be mainly due to a higher rate of heart attacks, strokes and cardiovascular deaths regardless of whether patients had heart disease or blockages in the arteries outside of the heart.”

The median modified Mediterranean diet score was 3.71. Patients with the lowest scores had a numerically higher incidence of cardiovascular and limb events compared to those with the highest scores, but the difference was not statistically significant.

“The Mediterranean diet is known to be protective against heart disease and our results trended towards this benefit but did not meet statistical significance,” said Dr. Wan. “This may be because our questionnaire did not contain all of the foods that characterize a Mediterranean diet, thus we had to use a modified score.”

“Dietary recommendations have challenges as many foods are not applicable across ethnic groups, countries of origin, and availability of resources,” states the paper.

“However, our study indicates that the emphasis should be shifted to improving overall dietary quality rather than specific food types by suggesting greater consumption of fruits, vegetables, nuts, higher fiber foods, choosing white over red meat, and consumption of minimally processed foods. This may improve the applicability to a larger general population with a variety of cultural backgrounds and simplify advice to patients.”

Professor Anand concluded, “Until now, our lifestyle advice to patients with PAD was to walk more and quit smoking. The results of this study enable us to add guidance on which foods to eat and which foods to avoid, which also applies to the many patients around the world with coronary disease.”

More information:

Darryl Wan et al, Dietary intake and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with chronic vascular disease: insights from the COMPASS trial cohort, European Journal of Preventive Cardiology (2023). DOI: 10.1093/eurjpc/zwad062

Journal information:

European Journal of Preventive Cardiology

Source: Read Full Article