Many parents say teens with anxiety, depression may benefit from peer confidants at school

An estimated one in five teenagers has symptoms of a mental health disorder such as depression or anxiety, and suicide is the second leading cause of death among teens.

But the first person a teen confides in may not always be an adult—they may prefer to talk to another teen.

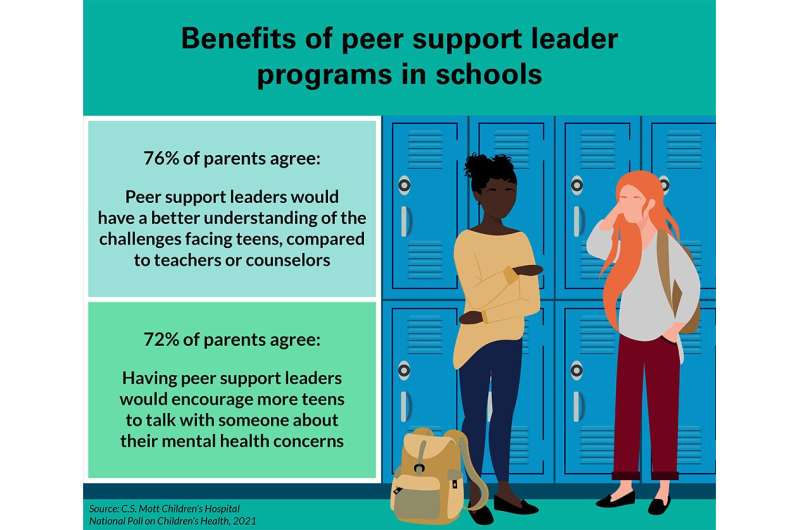

And three-quarters of parents in a new national poll think peers better understand teen challenges, compared to teachers or counselors in the school. The majority also agree that peer support leaders at school would encourage more teens to talk with someone about their mental health problems, according to the C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital National Poll on Children’s Health at Michigan Medicine.

“Peers may provide valuable support for fellow teens struggling with emotional issues because they can relate to each other,” says Mott Poll Co-Director Sarah Clark, M.P.H.

“Some teens may worry that their parents will overreact or not understand what they’re going through. Teachers and school counselors may also have limited time to talk with students in the middle of other responsibilities.”

Previous research suggests that as many as half of children and teens who have at least one treatable mental health disorder may not receive treatment due to several barriers. But teens who don’t have a diagnosed condition may still experience occasional problems with emotions, peer and family relationships, anxiety, academic challenges, substance abuse or other issues negatively impacting self-esteem.

These type of situations may increase risk of developing or triggering depression during tween and teen years, experts say.

Some schools have instituted peer support leaders to give teens safe channels to share problems. Teens who serve as mentors in these programs are trained with oversight from teachers, counselors or mental health professionals. They are available to talk with their fellow students on a walk-in basis at a designated place at school or by referral from school staff.

“We have seen strong examples of school programs that prepare teens to be good listeners and to identify warning signs of suicide or other serious problems,” Clark says.

“The peer support mentors’ role is to listen, suggest problem solving strategies, share information about resources, and, when appropriate, encourage their fellow student to seek help. The most essential task is to pick up on signs that suggest the student needs immediate attention, and to alert the adults overseeing the program. While this doesn’t replace the need for professional support, these programs offer young people a non-threatening way to start working through their problems.”

The nationally-representative poll report included responses from 1,000 parents of teens ages 13-18 about their views on programs like peer support leaders.

Weighing Benefits and Concerns of Peer Support

Most parents say they see benefits to peer mentor programs. Thirty-eight percent believe if their own teen was struggling with a mental health problem, their teen would likely talk to a peer support leader and 41% of parents say it’s possible their teen would take advantage of this option. Another 21% say it’s unlikely their child would seek support from a peer mentor.

However, parents did express some concerns about peers providing mental health support to fellow teens as well. Some worried about whether a peer would keep their teen’s information confidential (62%), if the peer leader would know when and how to inform adults about a problem (57%), if the peer leader would be able to tell if their teen needs immediate crisis help (53%), and if teens can be trained to provide this kind of support (47%).

“Some of parents’ biggest concerns pertained to whether the peer leader would be able to tell if their teen needed immediate professional intervention and how to initiate those next steps,” Clark says.

Despite these concerns, a third of parents still say they “definitely favor” having a peer support leaders program through their teen’s school, while 46% say they would probably support such a program.

A quarter of parents also say their teen’s school already has some type of peer support program—and these parents are twice as likely to favor such efforts.

“This suggests that parent support increases once they understand how peer support programs work,” Clark says. “Most parents agree with the rationale for peer support programs but may be uncertain until they see how they operate and benefit students.”

Two in three parents, or 64%, would also allow their teen to be trained as a peer support leader, recognizing the benefits to the community, the school and their child’s individual growth.

However, roughly half of parents worried whether there would be sufficient training and that their teen may feel responsible if something bad happened to a student using the program. About 30% weren’t sure if their teen was mature enough to serve as a peer support leader.

“Most parents approve of their teen being trained as a peer support leader, seeing it at as an opportunity to develop leadership skills and better understand the challenges that different teens face,” Clark says. “But many also wanted reassurance that teens in these roles would have the adult guidance and support necessary to deal with difficult emotional situations.”

“Close connection to knowledgeable adults is an essential part of any school-based peer mental health program, particularly in regards to suicide prevention,” she says.

Clark says parents of teens considering service as a peer support leader may want to learn more about the training and resources offered, including whether the peer support leaders receive counseling and support in the event of a negative outcome.

She adds that when it comes to young people’s mental health, “it takes a village” to support them and help identify warning signs that they may be in trouble.

Source: Read Full Article