From Abidjan to Jakarta, how the city is reinventing what we eat

From junk food to McDonaldization of society, the most derogatory remarks about what we eat are often linked with the urban space. For better or worse, cities are seen as the ultimate crossroads of food, nutritional and epidemiological transitions.

Be it in the global north or global south, the ultra-processed products and empty calories found in many diets can for trigger obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension and diet-related cancers related to the growing presence of chemicals in our food. Cities are hubs of commercial consumption, food industrialization via supermarkets where many imported international commodities are competitively marketed, and mirror the global Walmartization trend.

This process emerged in the global north before other parts of the world, and the major food corporations emerged in the West, so it is sometimes equated with the Westernization of diets. The nutritional structure of diets is certainly shifting in the same direction everywhere at different rates. The share of carbohydrates in energy intake is decreasing, that of lipids (fats) is increasing, and animal proteins are replacing those from vegetable sources, while the consumption of industrially processed products is soaring.

Yet eating is not just about consuming. People’s eating habits are influenced by global trends but also by their representations, spaces and local roots.

Socio-anthropological surveys involving fine-scale monitoring are focused on what people eat, how they organise themselves to do so, and what they say and think about it. Eating is much more than just a food-intake activity, even for the most vulnerable—it is also about pleasure, interacting with others, forging relationships with the environment, while building and shaping individual and collective identities.

City dwellers cope with contradictory injunctions

City dwellers constantly have to contend with a multitude of often contradictory regulatory standards regarding food. In Mexico, for instance, are currently in a double bind due to a paradoxical food injunction—it has one of the highest rates of obesity in the world, yet it has been promoting the country’s street food since it was recognized by UNESCO as part of the intangible cultural heritage of humanity.

Still, a deeper look reveals that nutritional standards may be interpreted differently in different social settings, and that people navigate the inherent contradiction between nutrition and heritage according to their personal food situations.

Global south-south chains

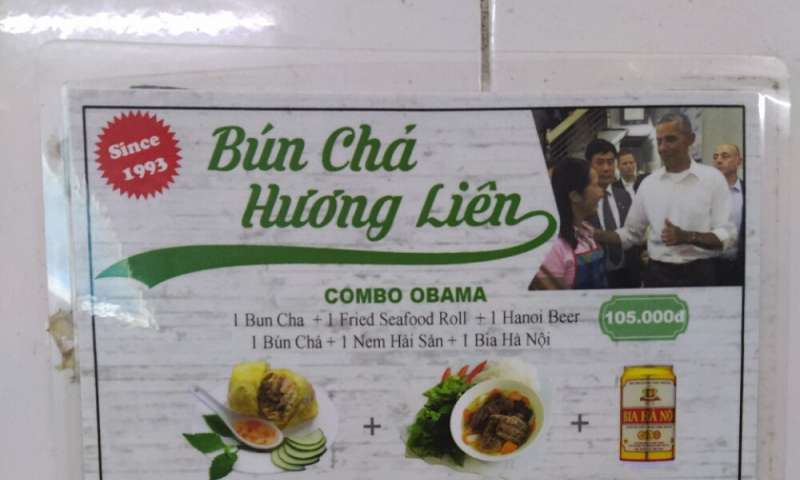

African, Latin American and Asian cities are currently in the throes of developing international supermarket and fast-food restaurant chains. While Hanoi’s first supermarket didn’t open until 1998, there are now dozens, including a mall with almost 150 shops. It opened its doors in 2015 and belongs to the South Korean Aeon retail chain.

Hungry Lion, a South African fast-food chain based on the KFC model, got its start in 1997 and now operates nearly 200 restaurants. It is owned by the Shoprite holding company (also headquartered in South Africa), which is Africa’s largest food retailer, with nearly 3,000 outlets. But the transitions under way in these urban food systems go far beyond this industrialization trend.

New cuisines on the rise

In large cities, new practices and cuisines are constantly being invented that are far removed from the strategies of major economic operators. In Jakarta (Indonesia), kampung – literally “villages”—are poor neighbourhoods where an informal economy reigns. They’re marked by a constant movement and mixing of populations, often recent migrants from rural areas. Many inhabitants do not cook at home due to a lack of equipment, space and time.

In these neighbourhoods, warung makan have sprung up, a kind of self-serve public kitchen where people bring their own dishware and benefit from flexible payment terms. They help maintain what are viewed as traditional and domestic food styles, while facilitating community food sociability.

The boundaries between domestic and commercial spheres, public and private spaces are thus blurred, so the food analysis scale has to be focused more in terms of housing blocks and neighbourhoods than households.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=urDIqahDOLw%3Fcolor%3Dwhite

Invention of urban-centered cuisines

Popular catering is fertile ground for culinary innovations, where tradeoffs between different regulatory standards emerge and combine. New dishes, often originating in working-class households, are regularly embraced by the middle class while sometimes becoming identity hallmarks for entire cities or even countries. Attiéké-garba exemplifies this trend in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire.

This popular dish hails from youth-friendly restaurants—known as garbadromes – located near the universities. It was initially invented in opposition to the antiseptic standards that were deemed non-African. Here, diners flaunt an urban and Ivorian identity by eating garba, a dish composed of attiéké (cassava couscous) and garnished with fried salted tuna. The meal is ideally served “wet”—generously doused with frying oil—and browned by successive cookings.

Despite regular claims that garba is Ivorian junk food, particularly because of the allegated unsanitary nature of the dish and the outlets where it is served, it is still a favourite dish in popular restaurants.

It was originally sold by migrants from Niger drawn to the vibrant Ivorian capital and then adopted by students. It is now seen as an emblem of Abidjan or even Ivorian identity identity.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=KNRfTB4OlWc%3Fcolor%3Dwhite

In Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso), bâbenda – originally a rural dish specific to the Mossi ethnic group—is gradually gaining status as an identity dish throughout the city, but its trajectory differs from that of garba.

A lean-season dish, it’s a porridge made of millet leftovers combined with leafy vegetables that emerge at the onset of the rainy season. Enhanced variants using crushed corn or broken rice instead of millet, which are readily available in the city, are now offered and enjoyed by people of ethnic groups other than the Mossi.

Some dishes fade while others are invented

Promoting the creativity of African, Latin American and Asian cities and their capacity to invent new foods can generate opposition to the view that places greater emphasis on the international market and capital dependence of these cities and on global Westernization.

While the two trends can be seen as being in opposition to each other, they’re in fact linked. As once traditional dishes disappear, new dishes are constantly being invented.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=wd9kBpea9As%3Fcolor%3Dwhite

Globalized cultures and food practices are clearly apparent cities of the global south, but this does not just reflect an erosion of local food systems.

Global products are being disseminated, but may be used in different ways in different cities and within cities in different social environments. In India, for instance, Maggi instant noodles have gained prominence in middle-class households through the character of the fictional “Maggi mother”. Her presence allows consumers to overcome social guilt about adopting this time-saving option, which otherwise might be seen as a transcendence of the role of the nurturing (and genuine) loving mother.

These local adaptation and reinterpretation processes have been analysed for the emblematic case of pizza.

Coexisting systems

Urbanization-related changes in food systems cannot be interpreted simply as a shift from domestic and artisanal to industrial systems.

Source: Read Full Article