Fluorescence Quenching

Fluorescence quenching is a physicochemical process that lowers the intensity of emitted light from fluorescent molecules.

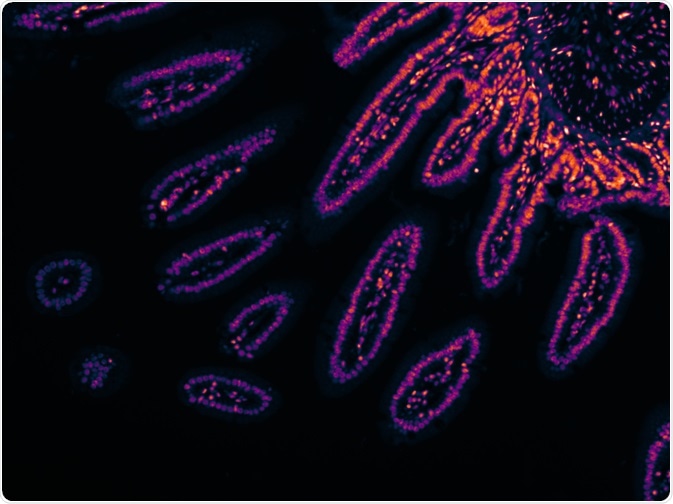

Virginie Thomas | Shutterstock

Virginie Thomas | Shutterstock

When a molecule absorbs light, electrons in its constituent atoms become excited and are promoted to a higher energy level. When electrons in this excited state lose energy and return to the ground state, they release this energy in the form of heat or radiation. Light emitted during this process is known as fluorescence, and the molecules that show this activity are called fluorophores.

Static quenching

Static quenching is caused by the formation of a complex between a fluorescent and a quenching molecule. The complex, once formed, is non-fluorescent. Formation of the complex takes place before any electron excitation occurs.

Dynamic quenching

Dynamic quenching is caused by interaction between two light-sensitive molecules; a donor and acceptor. The donor fluorophore transfers energy to the acceptor, which may then emit light itself or completely absorb the energy. In dynamic quenching, electron excitation takes place before the quenching process.

Mechanism of dynamic quenching

The Förster mechanism acts through non-radiative dipole-dipole coupling, where a negatively charged polar region of a molecule can pass an electron to a positively charged polar region of another molecule (intermolecular) or even itself (intramolecular). This can occur over distances of around 10 nm but becomes more likely the closer the dipoles are to one another at the rate of the inverse of the distance to the power of six.

Dexter mechanism

Dexter occurs when donor and acceptor molecules come so close that their electron orbitals overlap, which may be as close as 1 nm. This allows the excited electron of the donor molecule to move to an unoccupied orbital of the acceptor molecule, becoming its ground state. Simultaneously, an electron is transferred from the acceptor to the donor molecule, also in the ground state.

Excited dimer

An excited dimer is made up of two molecules with excited electrons or excimer (excited monomer). The combination of two excimers, which can be identical or different, and which would not normally form a complex unless in their excited state, create an exciplex (excited complex). When the electrons fall back to their ground state, this would lead to the emission of light and thus fluorescence. When the complex breaks up, it releases a longer wavelength (lower energy) of light.

Applications of fluorescence quenching

Fluorescence quenching can be used as an indicator of DNA hybridization, where fluorophore and quencher molecules are attached to the ends of single-strand DNA and close to one another, creating a loop. As the DNA hybridizes and pairs to another single-strand DNA chain, the fluorophore-quencher complex is pulled apart, allowing the fluorophore to produce light.

The Förster mechanism of fluorescence quenching can be used to infer the distance between donor and acceptor molecules, depending on the intensity of quenching. This determines the size or conformation of a protein and detects any interaction between proteins.

Sources

- Fluorescence Quenching.

- Excimers.

- Resonant electronic excitation energy transfer by Dexter mechanism in the quantum dot system.

- Förster resonance energy transfer.

- Nucleic acid-based fluorescent probes and their analytical potential.

Further Reading

- All Fluorescence Content

- What is Fluorescence Spectroscopy?

- How do Epifluorescence Microscopes Work?

- GFP-tagging in Fluorescence Microscopy

- Importance of Colocalization Studies

Last Updated: Jan 17, 2019

Written by

Michael Greenwood

Michael graduated from Manchester Metropolitan University with a B.Sc. in Chemistry in 2014, where he majored in organic, inorganic, physical and analytical chemistry. He is currently completing a Ph.D. on the design and production of gold nanoparticles able to act as multimodal anticancer agents, being both drug delivery platforms and radiation dose enhancers.

Source: Read Full Article