Despite progress, Black patients still less likely to get heart transplants

Black people in need of a new heart are less likely than their white peers to get a transplant, and when they do, they’re more likely to die afterward, according to new research.

The study, published Wednesday in the Journal of the American Heart Association, analyzed the impact of changes made in 2018 to how transplants are allocated with the aim of expanding availability.

That year, the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) revised its allocation system, striving to improve access to organs among the sickest patients and to reduce racial and regional disparities. The older system created longer waiting times for people in diverse, high-population cities, potentially affecting Black and Hispanic recipients disproportionately.

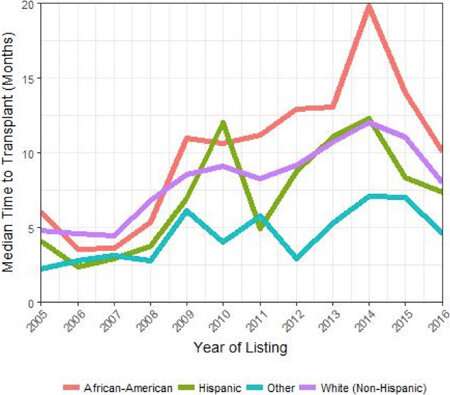

Evidence for this situation was reported in 2018 at the American Heart Association’s Scientific Sessions conference. The preliminary research suggested that between 2005 and 2016, Black patients experienced longer wait times for a heart transplant than other racial and ethnic groups.

For the new study, researchers analyzed heart recipient characteristics and outcomes for 32,353 people spanning about a decade of UNOS data from 2011–2020. They found that since the new transplant allocation system started in 2018, Black, Hispanic and white patients overall spent less time on waiting lists and had better chances of receiving a heart.

But some racial disparities remained.

Compared to their white counterparts, Black patients continued to have a 10% lower likelihood of transplantation. Researchers also found Black patients had a 14% higher risk of post-transplant death during the 10-year period, compared to white patients.

“We may be moving the needle towards more equity, but at the same time, we still have more work to do to reach the goal of offering heart transplant in an equitable fashion to all patients who need it,” said study co-author Dr. Sounok Sen.

Because the study was observational, it was impossible to pinpoint exact reasons for the racial disparities, said Sen, a cardiologist and assistant professor at Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut. The study also raises the issue of racial bias among medical professionals, Sen said.

“That’s something we know exists throughout the world. Whether it’s affecting transplant as well is a question we need to ask ourselves very carefully,” he said. “We need to look more closely at each of our programs both individually and also on a regional level.”

Sen said he’s hopeful emerging technologies will expand access and improve transplant success rates for everyone. He pointed to “organ care systems, often described as a ‘heart in a box,” that could extend the viability timeframe of the donor heart and allow us to travel farther to obtain suitable organs.”

He said another promising option is a “donation after circulatory death” transplant, or DCD transplant. That’s when a registered donor is not officially brain-dead but has a devastating, non-survivable neurologic injury and is withdrawn from life support with the family’s approval. DCD transplantation is expected to substantially increase the donor pool moving forward.

Dr. Errol Bush, who was not involved in the research, said it was the first study to evaluate changes in racial disparities since UNOS revised the allocation system. He said the results show “systemic racism” still exists when it comes to heart transplants.

“By highlighting these health care disparities, clinicians and policymakers can engage in dialog, support investigations, and develop and implement solutions to reduce them,” said Bush, an associate professor of surgery and surgical director of the Advanced Lung Disease and Lung Transplantation program at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

He said the new research underscores the need for achieving equity in the world of heart transplants.

Source: Read Full Article